I call it the Growth Mode Effect. Companies small and large are getting into financial trouble, ultimately filing for bankruptcy. As a supplier of automation equipment, specialty machine builders are some of our most important customers and at times our biggest worry. When their business models fail we also must deal with the consequences: financial losses due to unpaid invoices and the loss of...

I call it the Growth Mode Effect. Companies small and large are getting into financial trouble, ultimately filing for bankruptcy. As a supplier of automation equipment, specialty machine builders are some of our most important customers and at times our biggest worry. When their business models fail we also must deal with the consequences: financial losses due to unpaid invoices and the loss of another valued customer.

Once this happens, I ask myself if the demise of a once-strong company is an absolute must, given enough time. Fortunately the answer is no. Still, in many cases, the unfortunate flight into bankruptcy court was just too certain an outcome and most likely entirely avoidable.

Granted, I cannot claim to know about all the aspects of each company’s business strategy, but if the attitude shown towards changes in automation technology is indicative of their overall approach to change, then the unfortunate outcome seems inevitable. Here is how I see it:

Most of our customers are truly first-rate suppliers of highly complex automation solutions that allow their customers to turn out excellent products at very competitive prices. This collection of superlatives stems from the fact that motivated individuals once had excellent ideas, founded a company on those ideas and used modern control hardware to implement unique systems.

Everything from electrical drawings to mechanical solutions to efficient control algorithms had to be created. The resulting systems and machines offered the best function and reliability at the best possible price. And they were very successful.

They began to take on more projects; drawing from the automation solutions they developed, the company grew in size and sales volume. Machines were built quickly. Drawings simply had to be duplicated, PLC software modules copied and parts list for PLCs, sensors and other items reordered. Life was good, simple and the bottom line printed in black numbers.

While this worked for a number of years, the once-so-hot machines began to show signs of aging. The PLC they used from day one has since been surpassed by a cheaper and more powerful model. And by the way, the new and nimble competition that opened shop across town is using it. While these new players are investing time and money on new solutions, our established manufacturer unwisely continues to use dated hardware. What happens next is clear.

The once-powerful machine builder must compete by lowering prices or lose the business. Margins are getting thinner, allowing little time or money spent on updating equipment. A vicious spiral begins and eventually there is no margin left that could pay for the required change. By so doing, another player “saved itself” into oblivion. One more textbook example of how the well-known Product Life Cycle curve applies to industrial companies.

Granted this is oversimplified and a number of other factors are at play before the black bottom line turns into a nasty red. But you get the idea: Change or perish. I have seen it.

Avoiding the pitfalls

What can a machine builder do to avoid being another page in the book of once-great players? Let me answer that by using two hot-topic examples: PLCs, and networking I/O and safety devices.

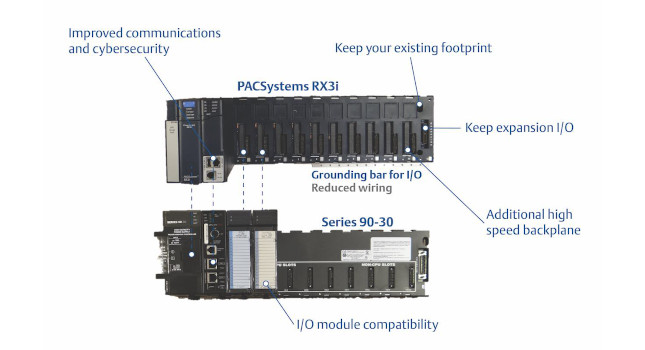

Years back, a major automation company introduced a successful modular family of small programmable controllers, significantly lowering the cost for a rock-solid control platform. Although according to that company it remains the gold standard in small logic controllers, it does not fare well against its more powerful and more recent bigger brother and the less costly micro-sized and compact PLC cousins. But, because the code modules written for the older PLC are not necessarily executing directly on the newer PLCs, this change costs money, providing an excellent excuse to forego a new control platform. If this is not reason enough to stick to the venerable gold standard, consider all the drawings that have to be updated.

Companies finding their offering in the Growth phase often decide that they simply cannot justify the necessary time and money for change, forgetting that on the other side of the Maturity hump lays the utter devastation called Decline.

Along with these new solutions come new networking technologies or lower cost scanner cards savings the older (“gold standard”) PLC user cannot hope to reap. For example, an AS-Interface scanner for that PLC is nearly 50% more costly than the modern equivalent for its bigger brother. In addition to cost, the new scanners are simpler to use and offer better diagnostics. A machine builder using the smaller cousins with the AS-Interface can rightfully claim better troubleshooting, resulting in higher machine availability. And that makes their customers happy.

To make matters even worse, many machine builders are still hardwiring sensors back to costly I/O cards. The time they spend pulling cables, stripping wires, terminating leads and labeling connections is staggering. Again, the Growth Mode Effect is at fault.

The concept of Networked Safety Devices is another example of how getting caught up in the Growth phase can be a sure path towards oblivion. This is not the time or place for a tutorial on how to use networked safety, but I must mention that AS-Interface Safety at Work has been approved and used for many years. Those who have used it only once have embraced the technology not because they wanted to do something different, but because they realized that the market demands a better (reads: lower cost) solution. Compared to machine builders that still rely on hardwire safety, Safety at Work users design faster, implement quicker and debug at an unprecedented pace. Adding or moving a safety device is speedy, effortless and does not require renegotiating the cost of the machine.

But the ever-present Growth Mode Effect persistently looms around the corner.

Solution advantages

I have personally given safety seminars explaining and demonstrating the advantages of networked safety to an interested engineering crowd. I saw smiling faces when I projected diagrams showing how much wire and installation time could be saved using this approach. Heads were bobbing when I outlined what a mess it can be when troubleshooting must relay on auxiliary contacts on e-stops. Eyes lit up when I showed them how the function of an otherwise unaltered collection of safety devices that was networked using AS-Interface was changed from activating a simple STOP function to performing a complex operation using muting – all within five minutes.

What happened next? I am glad to report that in many cases, the advantages of modern solutions were seen for what they are: a method enabling engineers to design better machines at a lower price.

I expect to visit these engineers for many years, always discussing their needs while informing them about new technologies. Unfortunately, there are always those who feel the transition is not possible. They have invested too much time in established, maybe even outdated technologies, procedures and systems. While I won’t give up informing them about modern trends, I am afraid that they may be yet another victim to the Growth Mode Effect.

| Author Information |

| Helge Hornis, Ph.D., is Intelligent Systems Manager for Pepperl+Fuchs, Twinsburg, OH. He can be reached at |