The past few years have seen some remarkable changes in lift trucks, the venerable workhorses of material handling. In what might be compared to the evolution from yesterday's muscle cars to today's high-performance vehicles, lift trucks have emerged from brawny weightlifters to strong and nimble athletes.

|

The past few years have seen some remarkable changes in lift trucks, the venerable workhorses of material handling. In what might be compared to the evolution from yesterday’s muscle cars to today’s high-performance vehicles, lift trucks have emerged from brawny weightlifters to strong and nimble athletes. To borrow a popular marketing phrase, “It’s not your father’s lift truck anymore.”

While the exterior remains familiar, the innards have changed substantially from just a few years ago. Nearly everything, it seems — from drives to seats has been analyzed and improved. Driven by the factors of safety, ergonomics, efficiency, productivity, and environment, manufacturers have introduced numerous improvements.

Drives

The biggest trend in electric trucks is the move to ac-power drives. AC trucks still use dc batteries, but an inverter is used to convert the dc current to 3-phase ac current. These drives offer a number of advantages. Among them:

-

Improved performance — faster acceleration, better gradeability, higher lift speeds, better and smoother response when reversing direction

-

Reduced maintenance — no brushes, commutators, contactors

-

Improved energy efficiency — up to 30% less energy consumption, more consistent operation over the life of a battery charge, opportunity for energy regeneration.

-

(For a detailed explanation of ac and dc lift truck drives, see PLANT ENGINEERING , January 2004, p 42.)

The advent of ac drives has also given rise to what is generally known as regenerative braking , although the energy is derived from more than just braking. The idea is that the inertial energy of the truck and mast can be converted to return energy to the battery, or to regenerate the charge. This is accomplished when the accelerator is released (coasting), when the brake is applied, when the operator is plugging (switching between forward and reverse), and when the mast is lowered.

Hydrostatic drives on IC trucks have made significant inroads in the European market and are likely to find a growing base in the U.S. In heavy-duty applications, hydrostatic drives are generally more efficient than the torque converter drives that are now standard.

IC emissions regulations

The big news in internal combustion engine (ICE) trucks is the new emissions standard that went into effect the first of this year. The standard affects all spark-ignition nonroad engines powered by gasoline, liquid propane gas, or compressed natural gas rated over 25 hp. Thus, it affects the vast majority of ICE lift tucks.

The standards starting this year are called Tier 1. The Tier 2 standards, which are even more stringent, go into effect in 2007. The standards do not apply to engines manufactured before January 1, 2004, so retrofitting is not necessary. Standards are even more stringent for trucks sold in California.

The new emissions standards are shown in the table below.

2004 lift truck emissions standards

HC+NOx CO Tier 1 (US) 4.0 g/hp-hr 50 g/hp-hr Tier 1 (CA) 3.0 g/hp-hr 37 g/hp-hr Truck manufacturers are meeting these standards by adopting many of the emission control technologies pioneered by automobile manufacturers. Chief among them are the use of a closed-loop carburetor system, addition of catalytic converters, and use of electronic fuel injection.

One caveat regarding the new engines has to do with fuel quality. Contaminants are frequently introduced into LP gas when it is being transported or transferred. There are no regulations regarding LP gas quality in the U.S. And in some trucks, poor-quality fuel can cause buildups that result in ignition problems. Since it is difficult to test for contaminants, plants must rely on LP gas suppliers to provide contaminant-free fuel.

California is actually looking to impose a standard for zero emissions on trucks less than 8000-lb capacity at some future date, which would mean the virtual elimination of IC trucks in those weight classes.

Electronics

Electronics have invaded the lift truck world in a big way, offering capabilities that were only a dream not many years ago. Customization of how things feel and work is now possible. Performance characteristics can be easily programmed and transferred from one truck to another. Drivers can be identified through passcodes, and detailed records of speeds or impacts can be kept. Checklists can be programmed for inspections before the truck will operate.

CANBUS

One of the most important innovations has been the development of the control area network, or CANBUS. With CANBUS, all of the sensors and controls on a truck can be integrated so that all systems are communicating with each other at all times for optimum performance. Truck wiring is simplified, and diagnostic capabilities are extended.

For example, using either onboard computers or a connected laptop, performance of vital parameters can be monitored and displayed in real time as the truck is run through its normal work activities. Temperatures, pressures, and electrical measurements are among the most common and useful.

In normal operations, CANBUS monitors critical functions of the vehicle. If a sensor begins to show that a critical parameter is approaching a level that would be detrimental to some component, the control system can recognize the condition, identify the problem to the operator, and change the performance of the vehicle to prevent damage to the component.

Maintenance

The new electronics also enable higher levels of preventive and predictive maintenance. Pressure drops across hydraulic filters can be used to determine when a filter is starting to clog and needs to be changed. Optical sensors can determine how dirty the engine oil is and signal the need for an oil change.

With the new emissions standards for ICE trucks, it is imperative that engines be properly adjusted. Now, sensing devices in the exhaust can measure emissions and send signals to the engine computer to adjust the carburetor or fuel injectors to maintain the proper balance of fuel to air for meeting the emissions requirements.

Controls

Many trucks are now using electronic rather than mechanical controls for mast operations. Some offer the option of controls in a seat armrest, greatly improving the ergonomics for operators. Another approach is a joystick-type control that combines all mast operations into a single device.

Another capability is to preprogram trucks for the use of various attachments. When an attachment is changed, controls are automatically reset for the new attachment.

Other electronic controls are being employed to increase safety as well as productivity. One company, for example, offers a stabilization system on 4-wheeled trucks that senses any instability during a turn and locks the rear axle to prevent further tipping.

For mast control, there are systems to prevent the mast from being tilted too far forward or from being tilted back to quickly, depending on the height. Another control will automatically level the forks as the mast is tilted forward, making it much easier to place and retrieve pallets at high levels.

Ergonomics/safety

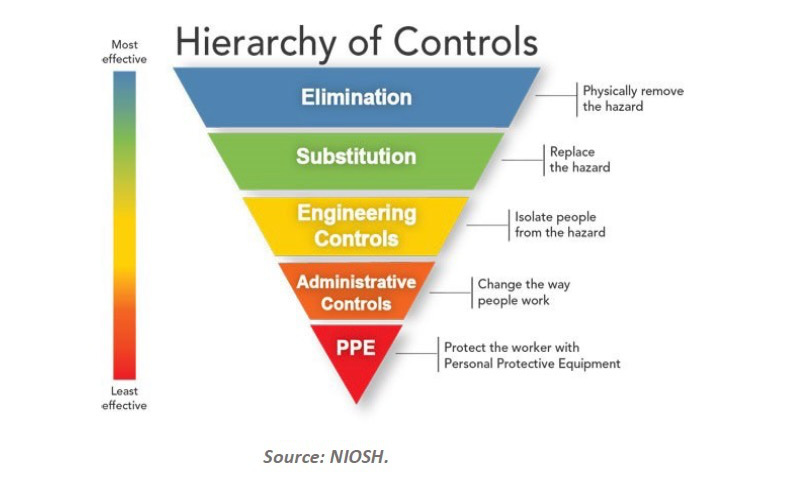

A 1990 study by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommended forklifts as one of five priority areas for machine safety research. OSHA statistics for 1998 regarding the number of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away from work show the total number of cases related to forklift use at 18,329. General “transportation accidents” represent the highest number of forklift-related injuries and illnesses with a total of 9335 cases.

With these kinds of data as an incentive, lift truck manufacturers have made major strides in overcoming the safety and ergonomic issues related to their equipment.

Visibility

Poor visibility is a key issue related to most lift truck designs. Poor visibility is a major cause of accidents involving lift trucks. One of the most common occurrences is hitting a pedestrian or object that the driver couldn’t see. High-visibility masts reduce this problem and are now standard equipment to improve both safety and productivity.

Even with improved masts, loads frequently obstruct forward vision, leaving operators with little choice but to drive backward. Driving backward helps solve the visibility problem, but it creates another one. Driving backwards requires the operator to rotate his/her neck and shoulders while keeping a foot on the pedals and a hand on the steering wheel. Serious long-term injuries can result.

Seat improvements

For both safety and driver comfort, swivel seats are becoming common. As a report by the Pulp and Paper Health and Safety Association in Canada points out: “Driving a lift truck backward for long periods of time can lead to low back, neck, and shoulder discomfort and injury. Not only does the physical performance of the driver suffer; this hinders productivity and increases lost time and compensation costs.” Swivel seats can improve worker postures and visibility when driving both forward and backward. The seatbelt should move with the seat so the driver is not fighting the belt restraint when driving in reverse. Retractable belts are preferred.

Since the first operator restraint system was introduced in 1983, all manufacturers have developed some kind of restraint system for their lift trucks. Restraint systems consist primarily of a seat with shoulder-height wings, re-tractable lap belt, and hip bolsters. Provision also needs to be made to keep the seat itself in place in case of a tipover. By keeping the operator inside the overhead guard frame, the driver is protected from the most dangerous aspect of a tipover, being pinned under the truck.

Trucks are now available with seat-connected switches that cut off the hydraulics system and/or return the transmission to neutral when the driver leaves the seat. The safety benefit is obvious.

Directional control pedals

Some manufacturers offer the benefit of a single control pedal for shifting between forward and reverse as well as acceleration. These pedals allow operators to control truck direction and speed without having to remove their hands from the steering wheel or hydraulic controls. Although not new, they are becoming more popular.

Vibration damping

Several studies have shown that vibration is a contributing factor to low back pain among lift truck drivers. Unfortunately, suspension seats are not a sufficient remedy for protecting operators from harmful whole-body vibration exposure. Other factors, such as truck weight, driver weight, load weight, truck speed, floor condition, and type of tires are a greater influence. Manufacturers are doing their part by improving engine mounts and suspension systems.

Word of caution

For all the wonderful technology being applied, there is one trend that requires buyers to be cautious. The new trucks are generally more capacity specific than their predecessors. This means that buyers should not automatically assume they can replace that old truck with a new one of the same capacity. Required loads and heights should be verified. Then vendors should be consulted to ensure the right match of truck to application.

Finally, the value of test driving should not be underestimated. Although operators shouldn’t necessarily have the last word on truck selection, their input is important. And with all the new features, it may not be easy to make the right selection without experiencing their feel.

More Info:

References

“The Ergonomics of Lift Trucks,” a technical report by the Pulp and Paper Health and Safety Association. pphsa.on.ca

“Emission Standards for New Nonroad Engines,” EPA Regulatory Announcement EPA420-F-02-037. epa.gov/otaq/regs/nonroad/2002/f02037.pdf

Contributors

PLANT ENGINEERING appreciates the assistance of the following companies who provided information and illustrations for this article:

Clark Material Handling Co. clarkmhc.com

Crown Equipment Corp. crown.com

Hyster Co. hysterusa.com

Jungheinrich Lift Truck Corp. jungheinrich.com

Nisson Forklift Corp. nissonforklift.com

The Raymond Corp. raymondcorp.com

Toyota Material Handling USA, Inc. toyotaforklift.com

Yale Materials Handling Corp. yale.com

Concept lift truck

The “Future Truck,” developed by Jungheinrich is a concept vehicle designed to address the problem of drivers having to twist in their seats to travel backward. On this truck, the entire driver compartment, including all controls, swivels 180 deg.

Hybrid vehicle

Described as a cross between an automatic guided vehicle (AGV) and a pallet truck, the Hyster HyBot may provide a hint of the future. Using a laser guidance system, the vehicle can be easily programmed to run from almost anywhere to anywhere in the plant along predetermined traffic routes. At each stop, local operators take manual control to load or unload the vehicle. A wireless communication system allows calling for the vehicle from specified locations or rerouting it at any time.

The system can also be set up to open and close doors along the vehicle’s path.