A plant electrical engineer designed the power wiring for the HVAC system in an addition at his facility. After the new area was occupied, several undersized wires leading to a fan-powered box in a ceiling cavity overheated.

A plant electrical engineer designed the power wiring for the HVAC system in an addition at his facility. After the new area was occupied, several undersized wires leading to a fan-powered box in a ceiling cavity overheated. The surrounding insulation caught fire. Claims against the engineer for property damage resulting from negligence exceeded $300,000. In addition, several people were hurt and the engineer was held responsible for bodily injury claims from the fire.

A fork lift operator was transporting a large metal coil when he hit an aboveground tank filled with hydrofluoric acid. Dangerous fumes were released into the community. Area residents and businesses were evacuated and several people were treated at a local hospital for fume inhalation. Claims for business interruptions and bodily injury amounted to nearly $100,000.

A maintenance mechanic was performing regular PM on a conveyor system when a portion gave way causing him a permanent disability from a leg injury. Although he had been following the conveyor manufacturer’s recommended procedures, he was not aware of a modification that had been made to the system earlier by the plant maintenance staff. His claims against the company and the plant engineer are still pending.

What do these three incidents have in common? They all involve the plant engineer or a department for which he is responsible in legal action. We live in a litigious society today. Lawsuits are commonplace, and sometime frivolous. And no matter how undesirable they may seem, they are a fact of life. With an ominous frequency, plant engineers are more and more finding they must consider the legal, as well as the engineering, side of the activities they manage.

Our litigious society

Odds are most plant engineers will never be party to a lawsuit. However, failure to be cognizant of the potential risks and their consequences can threaten a plant engineer’s very livelihood. If a catastrophic or injury producing incident occurs and the plant engineer is involved or responsible in any way, he may well be held accountable. A little knowledge can go a long way toward preventing unwanted and unpleasant actions.

Litigation arises in a number of ways: Through the action of governmental agencies such as OSHA and EPA, in the form of civil lawsuits brought by injured parties; and lately even in criminal actions. The plant engineer is immune from none of them.

Civil actions are most common and typically result from claims that a plant engineer made improper or negligent decisions regarding a piece of equipment, facility, or process, particularly if an injury occurs. In some cases, state laws (workers compensation laws, for example) provide some protection against legal action. But more and more, ways to circumvent those state laws are being sought and found, making employers, manufacturers, and just about anyone involved in an incident responsible for the outcome. Recently, industry has begun to fight back somewhat as manufacturing and engineering associations take steps to encourage tort reform both at the state and federal level (see, for example, the position paper of the IEEE at www. ieeeusa.org/forum/positions/ liability.html ).

The steps, however, are small ones, and despite the efforts to restrict the frequency of frivolous lawsuits, business and industry in general, and plant engineers in particular, need to be aware of what kinds of situations put them at risk to litigation and what they can do to protect themselves.

An ounce of prevention

The best defense a plant engineer can muster against any type of legal action is to take steps to manage engineering risks and prevent an actionable liability from occurring in the first place. First and foremost, companies must take responsibility for employing and training qualified, knowledgeable, and ethical people in plant engineering positions.

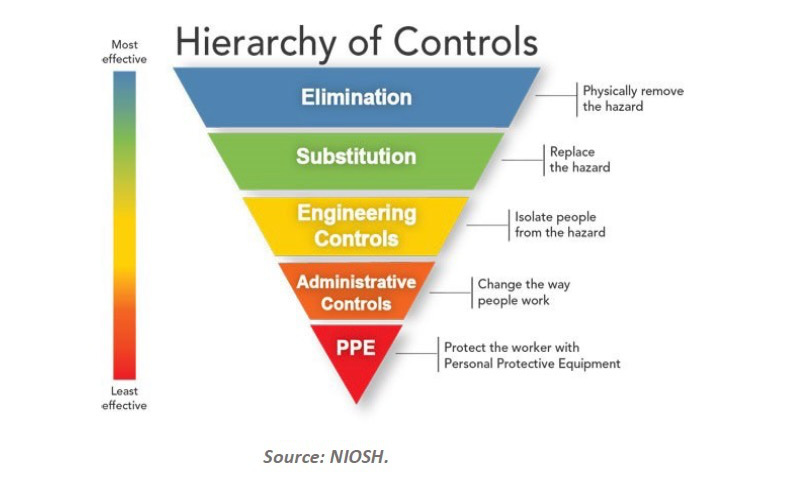

Next, they must support the plant engineer’s efforts to manage the risks and identify and then eliminate potential hazards. Risks in an industrial plant come in all shapes and sizes. Liabilities may arise from any aspect of plant operations, although many fall into the safety and environmental categories. In essence, the plant engineer should strive to apply the same preventive maintenance concepts customarily used for equipment to the prevention of potential liabilities. The following eleven points touch on some of the major areas to address when seeking to avoid or manage potential risks.

Take time to plan. Good planning is one of the best ways to avoid liability issues. Many liability situations result from lack of planning. If your plant does not have a disaster plan, now is the time to prepare one. If you have one and have not reviewed it in more than a year, do so now.

Identify and locate the potential liabilities in the plant. Survey the facility and determine areas that may contain trouble spots. (See the accompanying section on “Liability exposures for plant engineers” for a checklist to use as a starting point.) Safety and environmental concerns are potential trouble spots. Review regulations from OSHA and EPA. Check hazardous materials handling procedures. Examine aboveground and underground storage tanks, machine guarding, and personal protective equipment use, to name a few. Check wastewater discharge points, chemical and fuel storage areas, and housekeeping oversights that may lead to slips and trips. Performing environmental and safety audits are common tools for identifying potential problems and preventing possible liabilities.

Indoor air quality — or the lack of it — is an emerging area of concern as terms such as “sick building syndrome” come into popularity. If a lawsuit related to IAQ develops, the plant engineer will undoubtedly be involved because 80% of all IAQ problems have their roots in poor or inadequate maintenance. Finally, pay attention to employee work habits. Are they using the correct equipment and appropriate tools? Taking steps to encourage behavioral changes in employees reduces the plant engineer’s risk of being liable for unsafe practices.

Establish policies and procedures. Prudent plant management implements policies and procedures that acknowledge in writing that certain activities will not be tolerated because of liability. For example, one plant no longer designs or modifies any type of overhead lifting device or equipment used to pick up materials. These tasks must be done only by the companies who manufacture the systems or by a licensed engineering house. Another plant allows no modifications to any production equipment without the approval of the manufacturer or corporate engineering department. And anyone who makes an unauthorized change is responsible for it.

Preach the liability message routinely. Remind employees about liability regularly. Keeping the topic uppermost in their minds may prompt them to make that call to a vendor or to corporate or plant engineering before they act. Make them say, “I don’t really want to, but I guess I’d better check it out.”

Examine the governing issues. Before any project begins, determine the risk points. Are OSHA or EPA regulations or state and municipal codes involved? Set high standards and adhere to them. If outside contractors are involved, such procedures will weed out marginal firms and vendors.

Review the literature. Maintain a library of pertinent articles and information. Be aware of the issues and how the law is evolving. It takes time, but under the circumstances you don’t have time not to.

Maintain a network of contacts. Know where to go to find answers. Know whom to call, and know where to find the experts.

Use due diligence. Use the technical and regulatory knowledge presently available. If you’re applying that knowledge diligently, the chances of getting into trouble diminish. Gross negligence will not have occurred.

Meet with plant officials. Sit down with your corporate controller, financial officer, and whoever else is involved with the company’s liability and insurance packages. Determine and understand what is covered and what is not, should an incident occur. If the coverage appears insufficient, encourage management to increase it, to add a rider, or strengthen the package in some way to provide proper protection to engineering professionals. (See the accompanying section, “Gotcha covered: The insurance umbrella” for more specific information on insurance coverage.)

Learn how legal matters are handled at your company. Are attorneys on retainer? Does the company have counsel on staff? Does the legal staff understand plant activities? A discussion or meeting may be advisable to enable everyone to understand the situations the engineering and maintenance staff face.

Don’t wait for a lawsuit to make use of your legal counsel. Find out in advance the company’s policy on defending employees.

Best laid plans

If, despite all preventive efforts, an incident occurs, do not fail to document everything thoroughly. Lawsuits notoriously drag on for years. Write down what you know about the incident, even details that seem irrelevant. If you are asked about it later, a record is available. Don’t rely on a distant memory.

Consequences of operating lean and downsizing can lead to situations where claims and lawsuits may develop. Shortcuts are taken. The knowledgeable expert that was once on staff is no longer available. Outsourcing to firms that don’t know your industry or business can open the door to actionable events.

Under most insurance policies carried by companies today, ordinary on-the-job activities are covered. Of course, obviously illegal actions, or actions that employees should know are illegal, are not covered. There is no defense against knowingly committed illegal actions. Litigation difficulties usually arise when plant engineers find themselves in court over an issue they did not know was wrong or an action performed under the direction of management.

Defenses to specific actions, of course, rest with the legal counsel and vary with the facts of each individual case. However, attention today is focusing on a spate of criminal cases that involve liability issues in general and plant engineers in particular. Trends in the law are worth outlining here.

Most findings of criminal liability have involved federal environmental regulatory issues. Among those capturing the fancy of the media of late is U.S. vs Sinskey (119 F3rd 712, 8th Circuit, 1997). Here, two company employees — a plant engineer and plant manager — were criminally prosecuted and convicted, and their convictions upheld, for knowingly rendering inaccurate an effluent monitoring method.

Sinskey is not an isolated event. The courts have clarified over the past half dozen years in several cases that lack of knowledge of regulatory permitting or other requirements is no defense to criminal liability. In those cases, the courts have found that federal environmental statutes do not require specific intent — or mens rea , the specific knowledge of the illegality. Instead, all that is required to show a criminal violation is that the person knew the true character of what they were doing. In other words, knowingly performing an activity, as a matter of law, contrary to a regulatory requirement, was sufficient for a finding of criminal liability. Examples might be knowingly discharging pollutants into a river without a permit or intentionally disconnecting a treatment device that would otherwise control air emissions. An employee does not have to know specifically that he is violating an environmental requirement.

Although these decisions appear ominous on the surface — and indeed these matters should be taken seriously — experts cite mitigating factors to put these decisions in perspective. Oftentimes, cases in which plant executives are prosecuted by the government for criminal activities are deliberately publicized in the hope that the public will take notice and avoid such liabilities in the future. And in some cases involving governmental agencies, if a plant engineer is able to document that his actions were taken in response to or under the direction of his superior, and there is an absence of criminal intent, the courts prefer to restrict their prosecution to more senior executives.

Tracing the law

However, certain violations of federal statutes are considered so important to avoid that both Congress and the courts have taken the view that the specific intent typically required for a criminal violation is not required for federal environmental regulations criminal prosecutions. Only a few exceptions have been identified.

In a U.S. Court of Appeals case involving a gasoline service station, the owner had been discharging what he thought was water into a storm sewer. In point of fact, the water was contaminated with oil. He was prosecuted criminally for a knowing illegal discharge of contaminants without a permit. His defense, that he didn’t know he was discharging pollutants, was dismissed by the District Court. However, the decision was overturned by the appellate court, which stated the owner was operating under a mistake of fact .

It is important to recognize that mistake of fact should not be construed as a blanket defense in cases of environmental liability. Such circumstances must be proven to the satisfaction of the courts. The defense here is not a failure to know the action was a violation, but a failure to know the factual circumstances of the situation.

An industrial example might be a plant wastewater treatment facility required to provide advanced treatment before discharge. Everything done shows advanced treatment was used and that all discharge has been fully treated, yet a discharge of contaminants has occurred. A permit violation has occurred. However, if the operator can show he investigated the situation, that he was doing everything he should, and that the system was operating the way it should and being monitored appropriately, he should not be criminally liable under a mistake of fact type of defense.

Today, the mistake of fact is about the only defense the courts accept or acknowledge in this type of case. And at this time it is not considered a majority view. The other type of defense, the mistake of law or lack of knowledge defense such as that asserted in the Sinskey case, has not been allowed

Although sensational liability cases such as these receive considerable publicity, plant engineers should note that very few cases — either criminal or civil — reach the courtroom. Most are settled before they get that far. Criminal cases are pursued when the government believes some sort of harm has occurred. Unless fraud is apparent, a safety or health incident in which, say, a paperwork issue is the primary offense, is not likely to become a criminal case.

The conscientious plant engineer taking steps to do his job diligently has no need to push the panic button. However, if apprehension spawns conscientious efforts on the part of industry, the development will be viewed by the courts and the government as good.

As a matter of practice, plant engineers can help limit legal liabilities by alerting management to any inappropriate activities and by keeping impersonal, generic records. Although such actions may be considered controversial, conscientious employers should be willing to correct illegal or risk-producing activities, In addition, “whistleblower” statutes protect employees from any retribution.

Be prepared

What lies ahead for legal liabilities and risk management? Predicting the future is always perilous, but it appears that rapidly advancing technology will continue to open new avenues of risk. The recent trend to using PCs instead of PLCs for plant control is but one example. PCs allow easier system access, opening the way for the inexperienced worker to introduce changes that might endanger a process or its operators and lead to a liability situation. A change believed to be insignificant may turn out to have a major safety or security impact.

Can you keep hackers away from machine controls or out of sophisticated, automated processing systems? As networks grow and access to them increases, the problems they create have the potential to become a liability Pandora’s box. It is up to the plant engineer to provide the barriers and the protection.

Whether or not efforts to curb frivolous lawsuits are successful, opportunities for liability will remain a threat, albeit a controllable one. In the real world, it is impossible to avoid every potential risk. Some major incidents will occur. You may never find yourself involved in a lawsuit or defending yourself, your actions, or your company in a courtroom. But if you do, it pays to be ready.

Plant Engineering magazine acknowledges with appreciation the special input to this article provided by the following companies: The ECS Companies (Paul Dietrich, ECS Underwriting), Exton, PA, and the law firm of Kelley, Drye, and Warren (J. Barton Seitz), Washington, D.C. We also extend our appreciation to the following plant engineering professionals for their input to this article: A.S. (Migs) Damiani, CPE/F-AFE, Consultant, Rockville, MD; and A. Wayne Weaver, Manager, and Rex Appel, Associate Manager, Corporate Plant & Facilities Engineering, Dietrich Industries, Hammond, IN.

Good advice

This article is intended only as a general introduction to liability and risk management concepts and should not be considered a recommended plan for your particular operation. Liability issues must be considered in consultation with the plant’s risk manager, insurance carrier, and legal counsel. Plant Engineering magazine assumes no responsibility for any actions resulting from the use or application of this information.

Liability exposures for plant engineers

A number of situations can incur liabilities for both industrial plants and the engineers that manage them. Some possible areas of potential liabilities that can put facilities and their plant engineers at risk are noted here. This list should not be considered all-encompassing. Every plant operation is different and the variety of circumstances that may be encountered are infinite.

– Excessive air emissions (CO, NOx, VOCs, and particulate, for example) from a variety of equipment, including painting and plating lines, ovens, and boilers.

– Poor housekeeping and PM on pollution control devices.

– Improper waste storage and handling practices.

– Hazards from sludges generated by wastewater treatment operations.

– Poor underground and aboveground tank management programs.

– Indoor air quality exposures resulting from inadequate or improper maintenance or housekeeping.

– Improperly maintained electrical equipment (PCB-containing equipment and transformers, for example).

– Lack of emergency power to backup systems.

– Poor or inadequate fuel handling procedures.

– Undersized pumping systems for pressure lines.

– Improper handling of flammable paints, solvents, and other materials.

– Failure to establish adequate chemical storage and handling procedures.

– Negligent selection of materials or equipment.

– Unsafe conditions that could lead to slips and falls.

– Unapproved equipment modifications.

– Faulty design resulting in system inefficiencies, property damage, or bodily injury.

Gotcha covered: The insurance umbrella

Plant engineers have expressed a growing concern over the increasing number of lawsuits that have occurred in recent years. Indeed most of society has, and rightfully so. Engineers practicing even 20-yr ago were not confronted with the liabilities that they face today. Our litigious society, coupled with increasingly complex technologies, have made exposures to liabilities much more prevalent.

Protection from risk can be achieved in a number of ways. Taking steps to eliminate the exposure before it occurs is one. Another primary one is through insurance coverage. Insurance carriers typically offer a triage of risk management services to address liabilities: policies, risk prevention and control measures, and claims handling.

1. The policy. This document is a contract that protects companies and/or individuals from acts, errors, and omissions in the course of their work. The policy ensures that the company will have someone to respond to claims and pay for the retention of counsel to defend them if they are sued. Defense costs can be substantial, especially when complex matters and expertise may be required.

2. Risk prevention and control. In this area, carriers seek to assist the plant or facilities engineer in practicing good risk management. Through educational materials, training, and advice, the carrier helps companies handle and control exposures to liability. Many firms offer workshops, classroom training sessions, and similar assistance aimed at helping engineers understand insurance terms as well as avoid risks. Environmental hazards, health and safety matters, and appropriate subcontracting of work are among the issues covered.

3. Claims handling. If prevention and protection efforts fail and the plant is confronted with a problem, the carrier assists its policy holders in handling the claim and resolving the liability. Assistance may range from advice to negotiating a settlement to litigating the case.

Insurance is a critical must for all facilities, providing companies with much-needed defense coverage. Few claims ever reach actual litigation, with a majority settled out of court through negotiation. Most cases are civil suits commonly involving claims for economic damages. Property damage and bodily injury claims are much less frequent. The main stumbling block to the settlement of claims is lack of communication. With adequate communication initially and an understanding of the expectations by all, a majority of claims can be resolved amicably, issues of negligence notwithstanding.

Offerings of many insurance carriers are able to address a company’s complete range of liability needs. These offerings may include professional liability (which typically covers economic damages), general liability (which addresses property and casualty coverage, including damages from slips and falls, bodily injury, and destruction of property), workers’ compensation, and vehicle coverage. Although many plants are affiliated with several carriers, working with a single insurer streamlines the process and limits the number of contacts a plant must make in an emergency. Because gray areas exist in every policy, especially between professional and general liability coverages, having one company address both minimizes the possibility of omissions. In addition, many carriers discount premiums when multiple policies are maintained.

Insurance is a competitive industry, making it a buyer’s market. In the professional liability area alone, there are at least 35 carriers offering coverage. The corporation seeking special needs or services is likely to find what it is looking for with a little research. On the other side, every plant should expect to be scrutinized by the carrier before a policy is written.

An underwriter looks for specific qualities in any company under consideration. The plant or corporation can expect to fill out an application that provides a profile of the operation, including number of employees, number of engineers, engineering disciplines on staff, services being rendered, type of work being done, and other characteristics that might help determine expected exposures. Premiums vary primarily with degree of risk and size of business.

Plants can also expect to be asked for a loss history, generally covering the past 5 yr. Questions may include how much money has been paid in claims and what is the nature of the claims. High-risk operations or operations assessed as working beyond or outside their expertise can expect to pay higher premiums or, like a bad driver, be turned down as too high a risk.

In return, plant management should expect true integrated risk management. The carrier should meet with its clients regularly, especially when larger facilities are involved. Policies are typically renewed annually and should be reviewed and updated on a regular basis.

Getting started…

The best protection from liability and risk is to keep litigious situations from developing in the first place. A plant engineer’s primary resource should be the company’s own risk manager, insurance carrier, and legal counsel. However, an abundance of material on engineering liability is available for those interested in further education. Below are some web resources to get you started.

Legal:

www.kelleydrye.com – The international law firm of Kelley, Drye, and Warren employs some 300 lawyers to serve businesses across a wide range of industries. Its many practice areas draw strength from an interdisciplinary makeup, in particular in environmental law. Its publications button guides a browser to articles on a variety of topics including environmental, labor, and employee benefits.

www.seyfarth.com – Seyfarth, Fairweather & Geraldson, a firm of more than 400 attorneys nationwide, has one of the largest labor and employment practices in the nation. It provides a broad range of legal services in many areas, including contracts, environmental, safety and health, and litigation. The practice groups button leads the user to a variety of information, including publications, in such areas as environmental safety and health, labor and employment, and litigation.

www.w-p.com – The nationwide labor and employment firm of Wessels & Pautsch, P.C., offers up-to-the-minute advice, strategy, and training seminars on a wide variety of aspects of employee/employer relationships. The site is a wealth of information that includes a publications button and a virtual library that covers timely labor and employment law topics. Firm is listed in AM Best’s Insurance Directory of Recommended Insurance Attorneys and Adjusters .

Risk management/insurance:

www.ecsinc.com -The ECS Companies provide integrated environmental risk management services. The three firms, ECS Underwriting, ECS Risk Control, and ECS Claims Administrators, work together to manage the environmental exposures of their clients through insurance, risk control services, and expert claims management. Try ECS Risk Control’s facilities button for articles on IAQ, health and safety training, and more.

www.factorymutual.com – Factory Mutual operates under the direction of three major industrial and commercial property insurers: Allendale Insurance, Arkwright, and Protection Mutual. It provides services in the areas of property loss prevention and control engineering, research, and training. The educational resources button leads to a wealth of publications, videos, and resources on equipment, hazards, and disaster planning.

www.industrialrisk.com – HSB Industrial Risk Insurers has been providing loss prevention services for more than 100 yr. Access publication and protection guideline information through the loss prevention button on the main menu.

Associations/organizations:

www.engr.washington.edu/~us-epp/Pepl/pepl. html – The Professional Engineering Practice Liaison Program, part of the University of Washington College of Engineering, offers training opportunities and resources on ethical engineering practices for the professional engineer. A click on the EPP home button leads to more information on the school’s Engineering Professional Programs continuing education offerings.

www.ieee.org – The web site of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc., includes abundant material on such topics as professional liability insurance and tort and product liability reform. Search the site for such terms as liability to link to a wealth of information and articles on liability and risk management.

www.asse.org – Among the information on the web site of the American Society of Safety Engineers is a book on legal liability. The reference explains the legal risks for both corporations and individuals involved in managing safety and health situations. Navigate to the Technical Publications Index for more information.