As discussed last month in Part 1 of our look at TPM, “Total” and “Productive” are the methods by which organizations implements solutions to resolve issues associated with Machines, Manpower, Materials and Money. In Part 2, we explore the focus of improving each of these M’s within TPM.

As discussed last month in Part 1 of our look at TPM, “Total” and “Productive” are the methods by which organizations implements solutions to resolve issues associated with Machines, Manpower, Materials and Money. In Part 2, we explore the focus of improving each of these M’s within TPM. First, consider where TPM falls within the maturity continuum of the world-class production system.

The world-class production system

For many companies, TPM is a sole improvement strategy to increase productivity while reducing the overall cost of manufacturing. However, this way of thinking is a catalyst for failure. TPM is neither the beginning nor the end of the continuous improvement continuum. To be successful in your TPM endeavors; focusing on engaging senior leadership to own productivity; efforts to improve OEE; empowering operators to perform autonomous maintenance; and creating a culture of continuous improvement, your organization must first be in a maintainable state.

An organization that is truly reactive in its maintenance practices is unable to manage the improvements identified through TPM. Proactive maintenance is the foundation for TPM. Building on the platform of maintenance process stability, TPM is implemented to create standards of practice geared toward stabilizing the manufacturing process. Once your organization and its manufacturing process are stabilized through proactive maintenance and TPM, Lean manufacturing methods should eliminate waste and inefficiencies caused by excessive work-in-progress, human error or inconsistency of operating practices and less than optimum manufacturing schedules.

The ‘M’ in TPM

Regardless if the focus is holistically centered on improving the manufacturing business, or if the scope is reliability-centric, machines, manpower, materials and money are always the fundamental issues.

Machines — Focusing on improving “machines” is probably the most common strategic goal of TPM implementations. The obvious intent is to eliminate failures and breakdowns that impact single-pass production capacity and drive higher manufacturing costs. The mistake that many organizations make is having too much maintenance in their Total Productive “Machines” strategy.

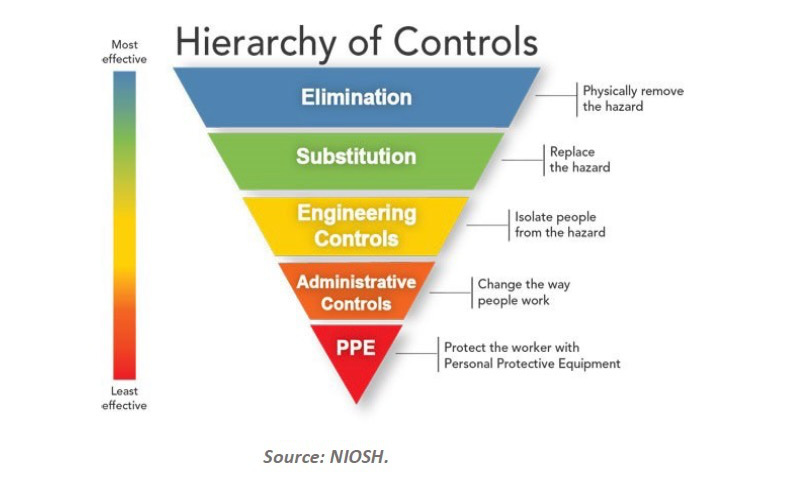

When designing solutions for greater machine reliability, your organization must consider the impact of each function — be that how the machine is designed, how maintenance and repair materials are procured and stored or the practices in place to operate and maintain the machine throughout its life cycle. Be cautious not to slip into the reactive culture of simply trying to add more maintenance or respond faster to breakdowns. Instead, focus proactively on failure elimination using techniques such as failure modes effects analysis to determine the types of failures common to similar machines, the severity of impact when a failure occurs, the frequency of failure and the controls required to mitigate the risk of failure.

One form of control is found in preventive and predictive maintenance, where, by routine inspections, cleanings or tests are performed to identify the potential for failure and determine the integrity of the machine. Additionally, developing a root-cause culture will provide a total focus on improving machine reliability. Establishing formalized Root-Cause Analysis business processes to record, trend, investigate and correct failures at the source of defect (cause) is a good starting point.

Manpower — This is not to say that TPM is designed to reduce headcount. To the contrary, it means that your organization is focusing on creating additional value through greater effective utilization of manpower. Within the Toyota Production System, value-added work is defined as any task that is performed in order to progress the “product” to final assembly.

In saying that, we must also reflect on the concept of efficiency, which can be defined as reducing the cost of production per unit in one of two ways: increasing production capacity, or reducing the cost of manufacturing. Therefore, systematic improvements in manpower should be focused on ensuring that “work” continually adds value by manufacturing more product or manufacturing the same amount of product at lower costs.

In TPM, the “manpower” focus is accomplished through standardization of work, elimination of non-value adding tasks and through continued training to improve labor skills to minimize defects caused by human error. This same approach applies to maintenance manpower. If maintenance costs are the focus of your TPM effort, then focused improvements in maintenance business processes geared toward determining the right work to perform at the right time and improving labor use through planning and scheduling is the key. The easiest way to control costs is to formalize the approval and prioritization process for requested work. Identifying the right work to do, and allowing an adequate amount of time to prepare for that work, significantly contributes to reducing the total cost of repair.

Materials — One of the biggest contributors to increased manufacturing costs is poor material control. Whether it’s the result of having insufficient raw material specification and quality; excess production WIP; or the result of excess, obsolete and/or non-fit for service maintenance and repair materials, “materials” should be considered as part of your TPM effort. Often times it is simply the methods by which materials are managed.

Again, included in your TPM should be a focus on developing business processes to manage and control inventories — from the point of procurement to point of use. Investigate the performance of your vendors and the effect they have on your organization’s ability to ensure reliable and consistent performance — either in manufacturing or in maintenance. Quantify excess and obsolete inventories, looking for the “hidden” or “reserve” stores, and consolidate materials where possible to reduce carrying costs, capital expenditures and the purchase of redundant spares.

Money — As you have read thus far, it all comes down to money. So, within the spirit of Total Productive “Money,” how conscience is your organization of minimizing manufacturing costs? Are planners and maintenance supervisors permitted to purchase directly from MRO vendors using credit cards, and without reconciliation to a work order? Are production and maintenance supervisors encouraged to procure contract labor in order to satisfy production and maintenance work schedules? How often are material inventories counted — physically — to identify shrink (depleted stock without record) and reconcile inventory value? Does procurement source materials based on lowest price, or lowest total cost of ownership?

“Money” can be found in everything we do throughout the process of manufacturing. However, most companies I visit focus narrowly on headcount, raw material and utilities. After all, these are our “controllable” costs. But more often than not, improvements in money can be driven by focusing on the processes by which your organization manages assets (machines).

Much like defects, cost is compounded based on the decisions made from the point when the asset is designed, through the procurement and installation phase and within your operating and maintenance practices. Part of the goal of your TPM effort should be to reduce the total cost of ownership, focusing holistically on reliability, availability and maintainability. Engaging your reliability and maintenance engineering staff to closely analyze life cycle costs and challenging them to re-engineer the strategies that ensure higher levels of machine reliability, availability to production and ease of maintainability (i.e. better accessibility, fewer maintenance activities, reduced time to repair) will provide savings over the life of your plant.

So the next time you are asked to define TPM, try “Total Productive Machines,” or “Total Productive Manpower” and I think you’ll find that your peers will understand more clearly the intent of your efforts. Then, challenge your organization to remain focused on the concepts of “Total” and “Productive” while tackling the “M” issues and you will greatly improve the success of your TPM implementation.

| Author Information |

| Darrin Wikoff is a principal consultant at Life Cycle Engineering specializing in project management, business processes re-engineering, RCM and CMMS/EAM. Contact him at [email protected] . |