Plant managers can get more out of the end process by looking at the whole, and not the components.

Industrial plants and facilities often buy machines and process skids for use in their production, packaging, and logistics operations. As an owner, director, or manager of a manufacturing plant, it’s important to purchase equipment that meets plant needs and can be easily integrated into existing production processes.

Many times, equipment purchases can get bogged down in component details, instead of focusing on performance requirements and specifications. Focusing on the performance requirements affecting the machine or process skid end product, and not the components running it, has advantages.

This focus allows the OEM machine or process skid builder to offer their lowest price, shortest delivery time, and best support. This confers a number of benefits to purchasers. They include:

- More bidders

- Lower cost

- Quicker lead time

- Faster start-up

- More reliable operation

- Better support.

Specifying performance requirements such as machine cycle rate; process flow rates and pressures; output configurations; finished product specifications; environmental, power, facility, safety, and dimensional requirements; and user interface requirements will go a long way toward realizing these benefits.

Understanding what to look for when it comes to specifying, installing, integrating, and maintaining OEM machines and process skids—with a particular focus on automation systems—can improve every step of the process, from specification to operation.

Performance-requirement advantages

Focusing on performance requirements instead of specifying components allows OEMs to stay in their comfort zone, providing benefits to the OEM and the purchaser. Perhaps the biggest advantage of focusing on performance is more bidders will come to the party, giving purchasers leverage in negotiations. OEMs know their standard equipment and its capabilities, so they can quickly ascertain if they meet the performance requirements. This will allow each OEM to provide a quotation that clearly confirms conformance to the performance requirements. Focusing on performance requirements instead of component specifications also allows each bidder to build the equipment the way they normally do, using their standard components and designs. It allows them to use their standard pricing, which is typically well-established and competitive.

By contrast, changes due to a purchaser’s detailed component specifications will force the OEM to develop a custom quotation, which is often just an educated guess with a fudge factor. Uncertainties are created for the OEM by hardware changes and required additional engineering and technician labor, inflating quoted prices, and lengthening lead times.

Providing detailed component specifications may require the OEM to redesign the automation system and other major assemblies. In the best case, the OEM will have in-house resources available to do this work, allowing them to price additions accurately.

Many OEMs won’t have the required in-house engineering resources available for custom designs. In this case, the OEM will typically hire a system integrator for control design and programming tasks, and a mechanical engineering firm for mechanical changes.

For example, instead of just releasing their standard drawings to build a control or electrical panel, OEMs will send design changes to an integrator. The integrator must then provide a quote for the design changes to the OEM, and a purchase order must be issued. Drawings also need to be updated and approved before parts can be ordered and the panel built. In parallel, similar activities may be taking place on the mechanical side of the machine design.

Having tight, rigid specifications for components will add cost and extend the schedule. Required additional design, approval, and purchasing will add weeks if not months to the schedule. Not only will the changes extend the schedule, but risk will also increase; as with major design changes, there is always the chance for rework, additional changes, and related delays.

Once a machine or process skid is purchased, it must be installed and commissioned.

Ease of installation and start-up

Equipment delivered based on the OEM’s standard design will result in quicker installation and start-up. The OEM’s technicians will be familiar with the automation system and other components, instead of trying to figure out how the customer-specified components operate. Any required changes can be performed quickly, as the OEM’s commissioning and start-up personnel will be very familiar with their standard designs (Figure 1).

This is particularly true when it comes to the automation system. Specifying a particular brand for an AC induction motor or a level switch might add cost and lead time, but it will have minimal impact on commissioning and start-up. But specifying a completely different automation system than the OEM’s standard, especially in terms of the operator interface and controller, will almost always result in issues.

Perhaps the biggest impact to the OEM, aside from changing their standard automation system, is in the area of software. There’s no easy way to simply port software programs written for one supplier’s controller to another, so most programs must be rewritten. This introduces bugs, which are often not found until the software is tested. A similar sequence of events takes place with respect to operator-interface software, which inevitably delays start-up.

Using a performance instead of a component specification provides many advantages, but there are also legitimate concerns, chief among them integration with existing equipment and systems.

Handling integration

Many plants feel the need to specify automation components to ease integration with existing plant automation systems. This was a very serious issue in the past, as many automation suppliers used proprietary protocols for communications, making integration with automation systems from other suppliers extremely difficult.

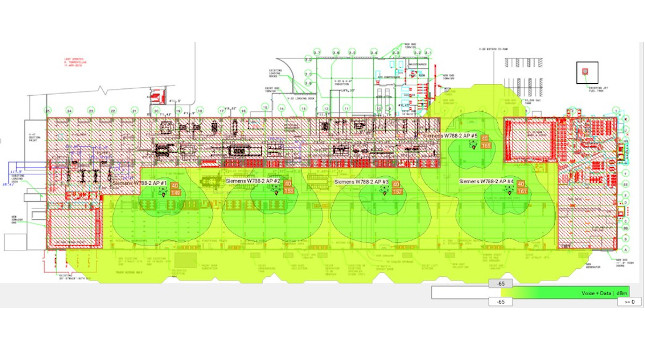

But the advent of open systems has addressed these issues, because all modern automation systems can now communicate with each other through standard networks, primarily Ethernet-based. Plant requirements can now focus on defining an open-system architecture, which will simplify the integration of new equipment with the overall plant automation system (Figure 2).

It’s not uncommon for the OEM to interface its equipment to other existing equipment and to plant automation systems. It is a requirement that the OEMs are familiar with, and have been meeting for years. In many instances, well-defined discrete and analog I/O signals are sufficient. However, using open digital-communication standards such as Ethernet is often a superior interface method, as the amount of data which can be exchanged over such a link is vast.

Therefore, purchasers should require each OEM to provide an Ethernet connection at the controller, the operator-interface device, or both. The purchaser should also specify compliance with the plant’s existing Ethernet protocol.

Common protocols include EtherNet/IP, Modbus TCP/IP, and Profinet. All of these Ethernet protocols provide the ability to transmit and receive large amounts of discrete, integer, floating-point, and string data—just what the plant needs now and in the future for integrating machines, process skids, and other production equipment.

The last piece of the communication puzzle is the communication schema, which defines the language used when different automation components talk to each other. With the purchased OEM equipment installed, integrated, and started up, maintenance and support come to the forefront.

OEM support

Although it may be more difficult for the plant to support and maintain machines and process skids with different automation systems, it’s still feasible—especially when the OEM is involved, which the plant should specify and require at the time of equipment purchase. Not only can OEMs install and integrate their standard design quicker, they can better support the equipment through warranties, support contracts, and service agreements.

The plant should specify that the OEM and the automaton supplier offer a full range of support, both on-site and remote. These support options will be more easily offered at a lower cost with the OEM’s standard design, and can include:

- OEM warranty

- Remote access by OEM

- OEM support contract

- Automation supplier support.

Once the OEM equipment is accepted at the plant, remote access is important. Free on-site support for the first year is common under equipment warranty, and many OEMs now offer free or low-cost support thereafter via remote access.

With proper remote access, almost all problems can be resolved quickly—and with today’s control systems, remote access should not be an add-on option, but instead built into the control system (Figure 3).

OEMs started with modems more than 20 years ago to gain remote access to the controller program. Over the years, remote access has been greatly improved by open standards such as Ethernet, and by the Internet. Whether it’s via a VPN allowing local-network access remotely, or an Internet-based program, remote access should be a specified requirement for the OEM.

Although the plant and the OEM will be the main sources of support for many items of equipment, the suppliers of the automation and other components often have a role to play. In some instances, plant personnel will be able to pinpoint problems to a specific component. In these cases, the most expeditious way to resolve the issue is often by contacting the supplier directly.

Some suppliers offer free or low-cost support, while others require expensive support contracts or a purchase order for time and material services before rendering assistance. For complex components like the operator interface and controller hardware and software, the plant’s purchasing team should ask the OEM what automation suppliers they are using, and ascertain the support offered by these suppliers. This information can then be used to make informed judgments prior to purchase.

When purchasing machines and process skids, it’s often best to only specify performance. Specifications beyond this level, particularly in terms of detailed component requirements, often create issues in terms of cost, delivery, start-up, and support. These issues negatively impact the OEM and, by extension, the purchaser.

Cindy Green is an industrial engineer at AutomationDirect where she provides assistance to a variety of product groups. She holds an M.S. in Manufacturing Systems Engineering from the University of Pittsburgh and a B.S. in Industrial Engineering from the University of Tennessee, and has more than 10 years of experience in manufacturing.