Researchers are developing methods to show how collaborative robots (cobots) can help and even improve human workers' roles in manufacturing.

Robotics Insights

- Robots are being used more often in manufacturing applications to handle dull, dirty and dangerous tasks and make them more automated.

- While this may give the impression they’re taking human jobs, it is often quite the opposite. If used well, robots and humans can work together and humans are given the freedom to perform tasks that are more fulfilling.

- Researchers providing actual examples of how robots can help humans in manufacturing is a good way to take an abstract idea and provide some context to it.

A future in which robot-powered automated manufacturing lines endlessly pump out products across industries sounds like a boon for efficiency and productivity.

It also feels more than a little dystopian, triggering fears of human workers being replaced by machines at an unprecedented scale.

However, Robert Radwin, a professor of industrial and systems engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he believes that vision is neither realistic nor prudent.

“Researchers are beginning to realize that a future workplace dominated by robots and completely devoid of human workers is not only impractical but undesirable, for a number of reasons,” he said. “We envision a workplace where workers won’t be replaced by robots, but rather where robots will assist workers in their jobs. That’s our goal.”

Radwin is working on several projects to devise strategies for introducing collaborative robots (or “cobots”) into manufacturing jobs in ways that enhance work—boosting overall productivity while reducing physical and mental workloads for human workers. To do so, he’s collaborating with companies like Wisconsin-based Mercury Marine, General Motors and Boeing, and teaming up with UW-Madison researchers in industrial and systems engineering, computer science, mechanical engineering and labor economics to consider the technical challenges, ergonomics considerations and employment policy issues.

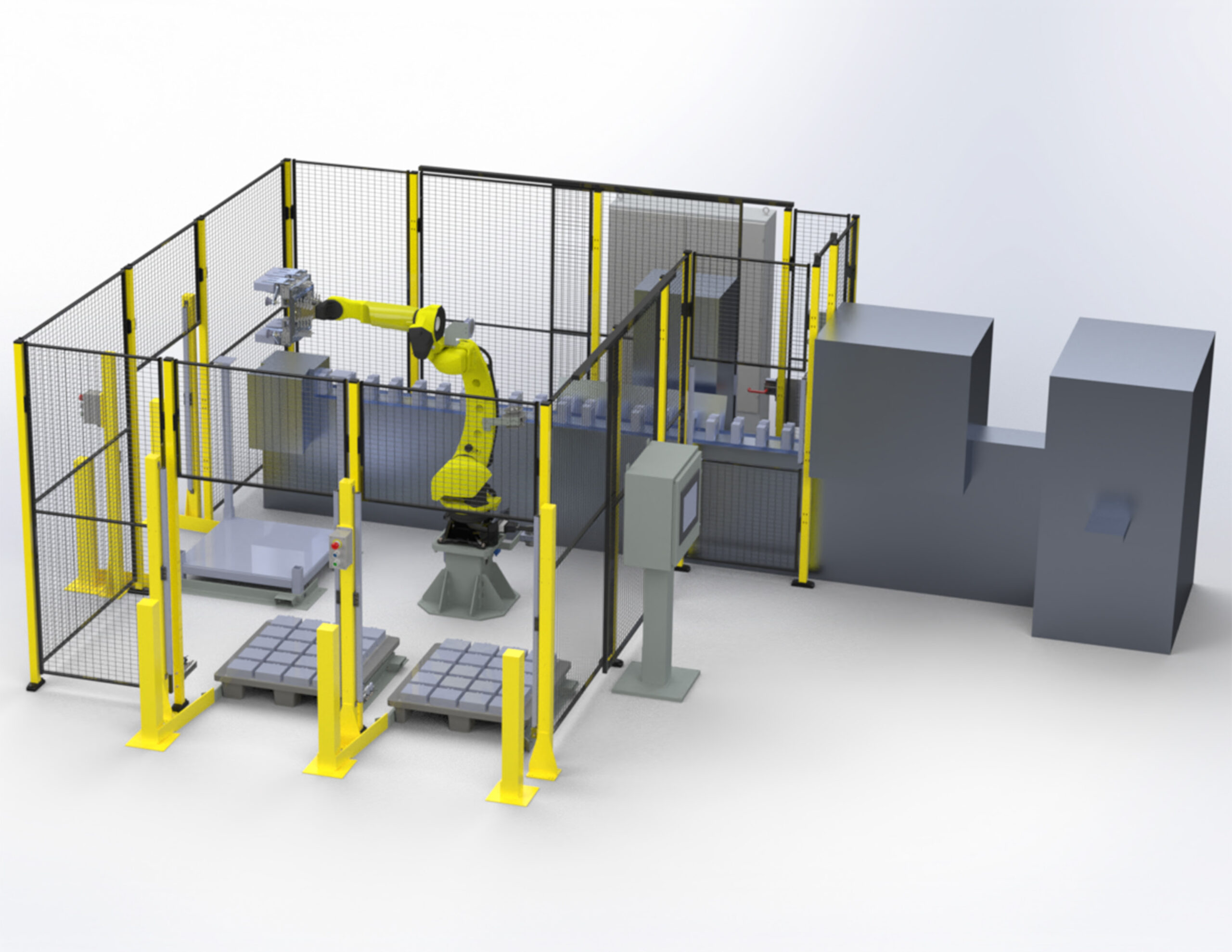

As opposed to industrial robots that function explicitly separate from human workers because of safety considerations, cobots are designed to operate in concert with humans. They move slower, deliver less brute force and include more sensors to avoid causing injury and can perform repetitive motions.

Through a series of National Science Foundation grants, Radwin is leading an effort to apply a data-driven methodology for evaluating jobs for human-robot collaboration—outlined in a March 2022 paper in the journal Human Factors—to real roles at Mercury Marine’s foundry and die-casting plant in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, and a General Motors assembly line. The research, part of NSF’s Future of Work at the Human-Technology Frontier program, will take a multidisciplinary approach with the help of Professors Bilge Mutlu (computer sciences), Shiyu Zhou (industrial and systems engineering) and Timothy Smeeding (public affairs), and Assistant Professor Lindsay Jacobs (public affairs).

Radwin is also part of a NASA-funded project led by Mutlu to apply a similar approach to aviation manufacturing with industry partner Boeing. Michael Zinn, an associate professor of mechanical engineering, is a collaborator, as is Michael Gleicher, a professor of computer sciences.

“Today employers are challenged to find employees,” Radwin said. “Right now, there’s a shortage of workers. It’s natural to think of trying to substitute workers with robots. But we think that, in fact, we can gain productivity and some of the benefits that employers are seeking by creating a better match between existing employees and automation.”

Radwin points to fears in the early 1970s that the introduction of ATMs would eliminate the need for bank tellers. Instead, the number of tellers has grown along with the expansion of bank branches. It turns out, in addition to making branch offices cheaper to operate with fewer tellers, ATMs handled tedious tasks like dispensing cash, freeing up tellers to assist customers with more complex requests—the sort of work humans are still better suited to handle.

“We get gratification from our work,” Radwin said, “and so that’s something that we think is an important aspect of creating jobs of the future that eliminate the bad stuff and enhance the good stuff, and at the same time improve productivity and make jobs better for workers, both physically and mentally.”

– Edited by Chris Vavra, web content manager, Control Engineering, CFE Media and Technology, [email protected].