Cornell University researchers are using optical lace to create a linked sensory network similar to a biological nervous system for robots to improve their actions.

A new stretchable optical lace could give soft robots an even softer touch.

The synthetic material, developed by Cornell University Ph.D. student Patricia Xu through the Organic Robotics Lab, creates a linked sensory network similar to a biological nervous system, which would enable robots to sense how they interact with their environment and adjust their actions accordingly.

“We want to have a way to measure stresses and strains for highly deformable objects, and we want to do it using the hardware itself, not vision,” said lab director Rob Shepherd, associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering. “A good way to think about it is from a biological perspective. A person can still feel their environment with their eyes closed, because they have sensors in their fingers that deform when their finger deforms. Robots can’t do that right now.”

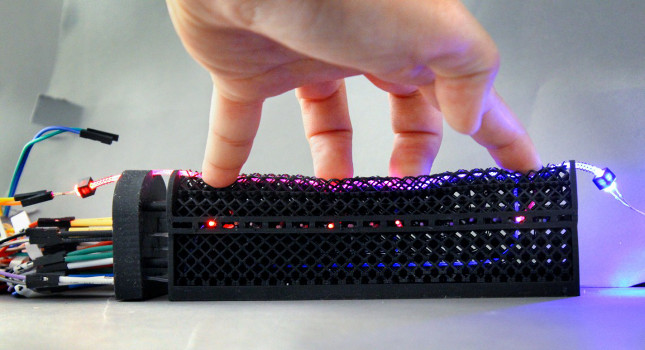

Shepherd’s lab previously created sensory foams that used optical fibers to detect such deformations. For the optical lace project, Xu used a flexible, porous lattice structure manufactured from 3-D-printed polyurethane; she threaded its core with stretchable optical fibers containing more than a dozen mechanosensors. She then attached an LED light to illuminate the fiber.

When she pressed the lattice structure at various points, the sensors were able to pinpoint changes in the photon flow.

“When the structure deforms, you have contact between the input line and the output lines, and the light jumps into these output loops in the structure, so you can tell where the contact is happening,” Xu said. “The intensity of this determines the intensity of the deformation itself.”

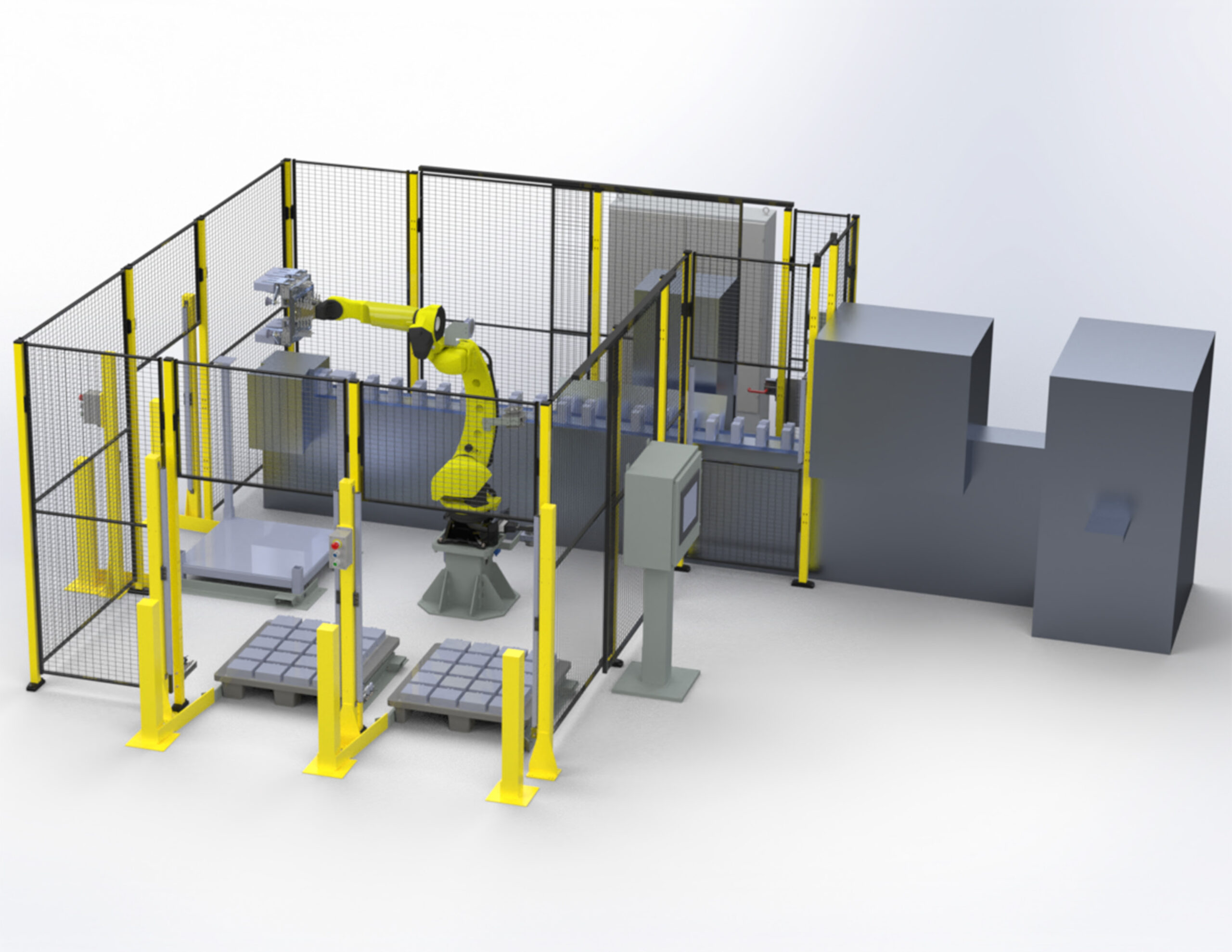

The optical lace would not be used as a skin coating for robots, Shepherd said, but would be more like the flesh itself. Robots fitted with the material would be a far cry from the cold, uncaring cyborgs of dystopian science fiction. They would be better suited for the health care industry, specifically beginning-of-life and end-of-life care, and manufacturing, he said.

“There’s a lot of people getting older, and there’s not as many young people to take care of them. So the idea that robots could help take care of the elderly is very real,” Shepherd said. “The robot would need to know its own shape in order to touch and hold and assist elderly people without damaging them. The same is true if you’re using a robot to assist in manufacturing. If they can feel what they’re touching, then that will improve their accuracy.”

While the optical lace does not have as much sensitivity as, say, a human fingertip that is jam-packed with nerve receptors, the material is more sensitive to touch than the human back. The material is washable, too, which leads to another application: Shepherd’s lab has launched a startup company to commercialize Xu’s sensors to make garments that can measure a person’s shape and movements for augmented reality training.

The researchers also plan to explore the potentials of incorporating machine learning to detect more complex deformations, like bending and twisting.

“I make models to calculate where the structure is being touched, and how much is being touched,” Xu said. “But in the future, when you have 30 times more sensors and they’re spread randomly throughout, that will be a lot harder to do. Machine learning will do it much faster.”

Even as robots become more aware of how they interact with the environment, humans still have a distinct advantage.

“We don’t know our own bodies as well as some robots know parts of their limbs and joints and fingers,” Shepherd said. “But we can still perform better than robots generally because we can deal with uncertainty through mechanical design, as well as neural architecture.”

The research was supported by grants from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the National Institutes of Health.

Cornell University

– Edited by Chris Vavra, production editor, Control Engineering, CFE Media, [email protected]. See more Control Engineering robotics stories.