Connecting plant floor data has been going on years, and the new wave of technology is seen more as an evolution of that process than a revolution of devices and IP addresses.

The Internet of Things. The Connected Factory. Industry 4.0. The media is abuzz with stories about how radical new technologies are going to change the world. But for the industrial Internet market, the story is one of evolution rather than revolution.

Despite the excitement, the vision of an IP address for every appliance in your house—the Internet of Refrigerators, if you will—is not going to translate into the ability to log in to every proximity switch or level transducer from your iPhone. These technologies will instead enable the next stage of the journey that began when engineers first made serial connections between devices within a control panel.

The development of industrial control technology has always been deeply tied to advances in connectivity. These advances in connectivity have come in stages, with communication first being established between devices in a panel, then between panels in a machine, then between machines in a cell, and now between cells in a factory and even factories in an organization or supply chain.

The victories of TCP/IP as a transport protocol and of Ethernet in the lower layers of the stack have helped drive the latter stages of this journey, and now the availability of cheap, reliable bandwidth between sites—via either wired or cellular connections—is allowing data to flow outside the boundaries of a business location.

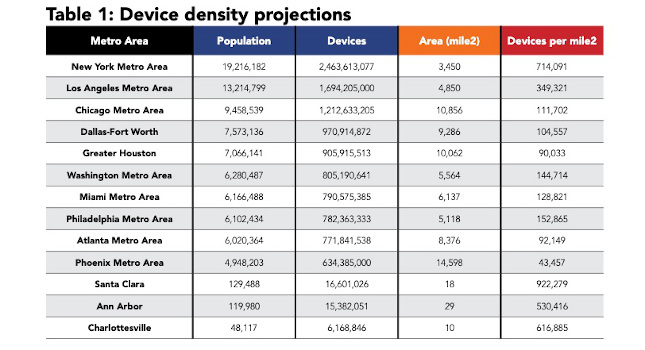

The discrete steps in this journey are reflected in the architecture that is and that should be adopted. A few years ago, the vision was for every device in the world to have its own unique address. IP version 4 (IPv4)—the basic protocol on which the Internet was built—has a theoretical limit of roughly four billion addresses, and it was predicted that the world would run out of addresses with the same alarming regularity as it is still predicted that we shall run out of oil. To divert this catastrophe, IP version 6 (IPv6) was created, expanding the address space to such an enormous degree that there isn’t even a name for the number of addresses it supports.

And yet outside certain important but limited realms, IPv6 has not caught on. This is partly because, as befits the committee-driven design process, the protocol is at least in the author’s opinion ridiculously more complicated than its elegant predecessor, with everything but the kitchen sink having been thrown into the specification.

Network address translation

But it is also because a solution to the address crisis was found in the form of network address translation (NAT). This technology allowed all of the devices on a network to access the Internet—or actually any other network—via a single IP address, with outbound connections all appearing to come from that IP and inbound connections being translated and remapped to specific devices on the internal network. NAT was a boon, removing the need for real IP addresses for each device on the network, and allowing the same IPs to be used again and again.

Had NAT simply been a compromise—a temporary hack to avoid address exhaustion – IPv6 probably would have spread more quickly. But NAT is more than just a work-around: it is the right way to design a network, hiding the internal components of a system and exposing to the next layer of the hierarchy only those functions and features that need to be accessible.

This is true in the consumer world—giving an address to every appliance in your house and exposing it to the Internet sounds great until some script kiddies turn off your refrigerator and crank up your hot tub in the middle of the night—but for the industrial world, it is essential. Good system design demands isolation, and this will apply just as much with the addition of the next layer of connectivity as it has always applied within the factory itself.

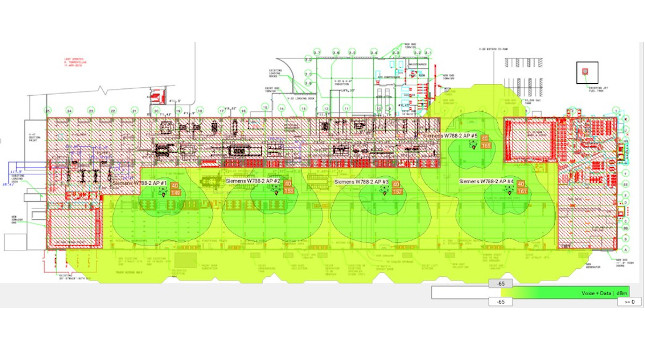

So what does this mean in reality? Most importantly, it means secure gateways at every level of the system. Within the control panel, a device will connect to all the other devices, and provide a single point of contact through which the panel’s contents can be securely accessed.

In Red Lion’s world, this device is the operator panel, as it forms a natural nexus of communication. HMIs with two Ethernet ports will provide NAT and gateway services, operating not only at the TCP/IP level but also in the application layer, concentrating data from multiple heterogeneous sources and exposing it via common industrial protocols. At higher layers in the organization, similar gateways will perform analogous functions, allowing access where it is required and segregating traffic into manageable domains.

Life in the cloud

Beyond the factory level, we’ll also see the cloud playing a role.

Even the need for a routable IP for a site will be removed, with site-level gateways establishing virtual private network (VPN) tunnels to cloud-based servers such that anyone wishing to access that site must connect to those same servers.

This is already happening with cellular data—Red Lion’s industrial networking products use this technique to work around limitations in cellular data plans that restrict inbound connections—but as with NAT, what started out as a matter of convenience is being recognized as a best practice and a technique that is equally applicable to wired networks.

The world is changing, then, but step by step, just as it has always done. Connectivity is spreading beyond the factory, and this will bring new challenges regarding network architecture and security. But the tools to address these problems are at hand, forged in earlier days as engineers fought the same issues at lower levels within the communication hierarchy.

The Internet of Things—a phrase beloved of cell phone salesmen who realized that everyone and their dog already had an iPhone and their sales commissions were in danger—is real, but it is not about accessing anything from everywhere. This is about accessing what is necessary from where it is proper. The right communication infrastructure will ensure that this is exactly what happens.

Mike Granby is president of Red Lion Controls, a global provider of communication, monitoring, and control solutions for industrial automation and networking. For more information, please visit www.redlion.net.

Red Lion Controls is a CSIA member as of 2/26/2015